“I'M DOING IT FOR THE SAKE OF SPREADING IDEAS:”An Interview with Jon Active

The Daily Grind at Active Distribution

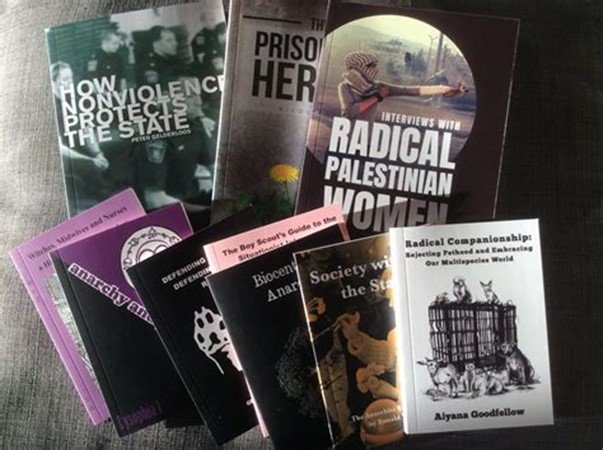

Editorial Note: Continuing in the trajectory of interviewing legends from last week, we turn to “Jon Active.” Jon started Active Distribution, as discussed below, in the late 1980s and with collaborators continues into the present. Based in the UK, Active Distribution has remained a staple in distributing anarchist zines, pamphlets and books and has done well to make English language material available in Europe. Jon has supported and helped many over the years by setting up distros, and offers the most affordable not-for-profit books and pamphlets, with some recent titles worthy of mention: The Failure of Non-Violence by Peter Gelderloos, Herbalism and State Violence by Nicole Rose and particularly relevant right now Palestinian Reader (Incomplete) and Interviews with Radical Palestinian Women. There are countless of other incredible books and pamphlets that are worth checking out and, through Jon and his collaborators labor, made available at the cheapest possible prices. We cannot stress enough our appreciation for Active over the years, and are pleased to talk with Jon and learn more about his interests, struggles and projects.

****

Alexander Dunlap (AD): What led you to start Active Distribution?

Jon Active (JA): What inspired me to start Active Distribution was the fact that I got turned on to the notion of anarchism by punk rock, specifically anarchist punk rock and Crass. One of the first records I ever got was stations, not stations, Feeding the 5000 sometime around 1980, I think. And that made me realize that there was something more to the word anarchy than what I'd always thought it was before, which was basically the BBC News definition of chaos and disorder. And so, because of the Crass lyrics, I went down to the local radical book shop in Leicester and got some magazines Plain Loco and some other ones which don't exist anymore, and a copy of Maldetesta’s Anarchy, little booklet by Freedom Press. And that was it; That was the beginning of the end. From then on, I've been a diehard anarchist. No stopping me. Never give up, etc. So, if that worked for me, I have this optimistic notion that maybe it could work for other people. And yeah, so that's why I started Active Distribution. Poison Girls helped me realize, or shall we say, that there's a very good chance that there won't be an anarchist revolution in my lifetime, no matter how many books I sell or no matter how many protests I go on, but I may well help inspire other individuals to have their own personal revolutions, a bit like I did back in all those years ago. So yeah, that's why I do Active Distribution.

AD: You were inspired by Crass, punk and DIY ethics, but what are your top ten favorite punk bands?

JA: I like punk bands for different reasons. I like some punk bands purely because they sound good. I have the first Skrewdriver seven inch [pre-fascist], because it sounds good. I even listen to Plasmatics and stuff like that even if the lyrics are pretty stupid. I don't support them. I don't wear T-shirts or whatever by those bands, but I kind of like them, just for the sound. But in order to put a band in my top 10, then they've got to be a band which inspires me and speaks to me, and, you know, makes me want to move, but move with a kind of passion. And that passion is normally some kind of expression of anger and whatever, which I have always felt at the world situation. The Top 10 bands also depend on when you talk to me, because they have changed a little bit, partly because I discovered new ones of late, although not so many new ones. The first band I ever really liked, which I fell in love with, was the Ruts because they just sound awesome. They were kind of political, not anarchists, but, you know, they were there very much in the anti-racism movement.

So, after The Ruts were The Damned. I Loved the Damned. I enjoyed myself at gigs in ways which I could only describe as being close to some type of sexual experience—just marvelous. Loved it. And then, The Damned were a little political, but not seriously (maybe that is unfair… I have seen The Damned at anti-nuclear things and at big free anti-fascist benefit concerts, even a big one in Brockwell park in London), but they expressed a lot about what 1970s-1980s UK was about with great songs, songs and tunes which make you want to jump up and down. And then, we have bands like The Dead Kennedys, just genius lyrics, wonderful sound, again, stuff you want to jump up and down to and with a really great cutting edge of cynicism about politics and stuff. And of course, you know, I began, I really valued Crass for what they were saying. And sometimes I was kind of like: “You know, how much do I actually like this music? …. I saw Crass in 1984. I didn't jump up down. I stood there and watched because it was such an important spectacle and I didn't need to be jumping up and down to that gig. It was something different, it was something significant, it was something that changed me.

Thing is sadly… and this was something I was warned about, shall we say, from Poison Girl lyrics and other people, is I've met and sometimes become friends with quite a lot of people from bands who I considered really important or really cool or whatever, to me, and sometimes they've turned out to be seriously disappointing, or they've gradually become disappointing. So, without naming names, let's just say there are not a lot of bands left who I really feel represent now, what they did then, which was so inspiring to me. This is one of the reasons why nowadays I'm quite happy to say that bands, like The Damned, are really important to me. Because even though they don't mean the same to me as, say, Omega Tribe or The Mob politically, back then; nowadays, you know, it doesn't really make a lot of difference to me in terms of the actual band. Because, yeah… it doesn't mean the same thing anymore. And that's not because I changed (even if I have a bit).

· The Ruts

· Crass

· Slime

· Laibach

Jon and his cat partner

AD: Alright, these are some important classics, the political significant of The Crass/Poison Girls 7” Split cannot be underestimated. Its great to hear what fuels your projects! …How long have you been doing DIY distribution and publishing and how have you seen it change over the years?

JA: I think I did my first stall selling badges and leaflets and some booklets about nuclear war and Northern Ireland back in the 1984 in Leicester; but I didn't really get going until I was at university. I think that was 1985-86, when I helped started anarchist group with some other people, did a paper called Black Sheep, Swansea [Wales]. We were doing Black Sheep, and I started going to London every other weekend, getting books from Freedom Press and Housman’s. I would mainly get the books from the basement of Housmans’, where a guy called Malcolm ran a kind of anarchist Grotto in the basement [laughing]. And that's where Ramsay from AK Press and I would sometimes meet. He would be coming down from Scotland, from Stirling, to pick up books that he was taking them back on the train, and I was hitchhiking up and down the M4 from Wales, doing the same thing. And we both literally started at the same time. Anyway, that's when I started doing DIY distribution. The publishing… the first thing I published was actually co-production with Ramsey from AK Press, before either of us had our logos sorted out. Malcolm, from Housmans, did a thing called Dark Star, but this booklet was under the name Violitte Noizzeres. And the book was a copy of Catechism the Revolutionist by Sergey Nechayev, which Malcolm was very keen to see in a booklet version. I thought it was an interesting text. And I actually put that together pre-computer times, done on a typesetting machine and cut and paste. A5 booklet, 45 pence cover price. It must have been 1990 or something like that. I'm not sure.

How have I seen it change over the years? Well, let's just say, when I started doing distro, it was part of the whole anarchist punk scene and there were a lot of rules. If you were a DIY distro in that scene, then it was very important that you're seen to be not profiting out of it. Which I patently wasn't, but it kind of got, you know, quite extreme in some cases. I used to get a real bollocking [e.g. angry words] from people if you didn't send their glued stamps back or ‘soap the stamps’ back to them, because that meant you were collaborating the system, because they lost the re-use of the postage. For those of you who don't know what soaping the stamp means, that's when you buy a stamp from a post office, you put it on your envelope, and then you put a layer of soap or something over it, so that when they stamp it you can just wipe it off and use a stamp again. That no longer works, of course, nowadays, but back then, it did. Although what happened, people who did it regularly, actually got a notification from the post office that they were aware of this, and they would take actions if it continued. I didn't get that, but someone I was working with got that letter, and I realized that it wasn’t working anymore.

But yeah, so that kind of thing was a feature of early distro, but to be honest, I really valued that whole nonprofit ethic that's been the kind of central theme for me ever since and to this day. Because, yeah, I hated the idea that people would think I was, you know, selling things in order to make money, because I wasn't. I'm doing it for the sake of spreading the ideas. Many people do not believes this, and the only way you can actually convince them is by selling things cheaply, at a not-for-profit price. Then obviously, you're not making any money, which is what I do. Active publishing doesn't make any money, and people are amazed at the prices of our [Active Distribution] books, but there you go. Regardless, plenty of people would always make snide comments about how I was raking in money from the distro, probably because there I was at many [punk] gig in London, doing a stall selling things as a and not drinking, and my detractors were standing around getting pissed and seeing me taking 1.50£ for copies of Maximum RockNRoll and therefore I was obviously raking it in. So yeah, that's why the nonprofit ethic is important to me. And the other thing is that, you know, people like Malatesta, Kropotkin and comrades who fought in a Spanish Civil War. They didn't do that in order to make money. They didn't do that in order to have a, you know, a comfortable existence inside the capitalist system. They did it because they were fighting for revolution. And the idea that I could be somehow trying to do the same thing, but making money out of it, just feels wrong. And that's not me having ‘a go’[or pointing] at people who do live from similar things. It's just the way I feel about it.

It's changed over the years because basically, there are very few distros left or there are very few distros which are of the same nature as there were back in the 1980s-1990s then there was a plethora of little anarchist DIY ventures, either selling records or selling zines, or zines and records, and some like us selling books and whatever. And obviously, ones like AK Press who were just selling books. A few of those, or a couple of those, like, aka, grew and became businesses, which were, you know, serious and publishing, lots of stuff. Most of the others just disappeared. Some turned out, turned into just record distributions. There is nothing necessary wrong with that, but the record kind of thing kind of became very much, well, in my opinion, became acollectors’ thing and very much kind of a music thing, as opposed to being about revolutionary music. But hey, maybe that's just me being cynical, or maybe that's just what actually happened, but, yeah, it changed generationally.

For example, I went on tour with a band last year, I took my stall to sell books at gigs, and I was amused; a whole bunch of people from, shall we say, a generation or two younger than me were like: “Wow, it's really good to have stalls at gigs. What a great idea.” I'm like: “That's fucking hilarious. There always were stalls at gigs!” You know, back in the day when I was around doing selling books and going on tours with bands in the 1990s and early 2000s but apparently, not so much anymore. So, I don't know what that says. Maybe the scene isn't as political as it was. Or maybe people don't have the freedom, to do the kind of thing which I was able to do. It's not so easy anymore. It’s harder to squat. We don’t have the same benefit system, which we used to have in the UK. It has changed. You know, as good as it was [laughter!].

Jon and one member of his cat gang.

AD: Okay, you are seeing ‘the wheel’ get reinvented again with tabling books and zines at gigs! Aside from the music itself, tabling was always a way for punk and (anti-)politics to unite and expand. Similar to how you have seen things change, You went to university and studied, if I remember correctly, anthropology. How have you seen academia and/or university hinder or advance liberatory ideas?

JA: Yeah, if I remember rightly, I did study anthropology [Laughter]. Oh, dear. I remember thinking: “Ah, I should maintain this, this level of knowledge about anthropology. I should continue it. I should read some of the anthropology journals and that kind of thing…. But hey, I didn't! And I moved from the hallowed corridors of Swansea University to the squats of Hackney [London], and within a couple of years, I was well aware that my vocabulary had had lessened, shall we say, or dropped in its sophistication….The University was liberating for me because I was one of those lucky bastards who was at university back in the days when you got grants and money from your parents, if your parents were wealthy enough, and so basically, I went to university because it was, like three years when I didn't have to get a job. I didn't like the idea having to get a job. So that's why I went to university, and I fucked around most of the time doing anarchist things and hitchhiking up to London to be with my girlfriend and going to gigs and getting books and organizing concerts and stuff in in Swansea. And yeah, I did a degree in anthropology, and I managed to pass the end of it, but I wasn't exactly a conscientious student, and so from that point of view, the experience of being a university was quite liberating for me. I intended to study philosophy. I ended up studying anthropology because I was well feedup by the philosophy tutor who was obviously more interested in impressing some of the attractive girls in the tutorial than he was really in teaching everybody in the room. And the woman who was teaching anthropology was really interesting. And she, you know, she generally inspired quite a few of us to study and to be interested in the subject and anthropology, it turned out, was a real corker for anarchism. Because, yeah, it was, you know, it was all about the principles of trying to be objective, and recognizing your internal biases and all that kind of stuff, and your and then looking at how societies functioned and especially smaller-scale societies. So yeah, anthropology was a good for me.

As for the wider discussion about academia, I am well aware of all kinds of criticisms of it from an anarchist point of view, but I am not in touch withhow it functions nowadays. I'm not, not sure if academia really is such a negative thing, as some people pointed out to be. I think there are things which a lot worse. I am not a fan of academic writing and style. I find it very exclusionary, andit pisses me off when people talk about anarchism in such a way that most people can't understand what they fucking talking about. But you know, that's what some people do, and I suppose it might get through to some people, just like Class War papers and Conflict will got through to other people in other ways.

I think my overall experience of witnessing or dealing with people who have been through, shall we say, the university system or academia in some form, tends to be that they have had the enthusiasm for activism kind of knocked out of them by the process of recognizing all the different arguments and the kind of sense that things never change, and that kind of realization and it’s apparent futility. I think it would be good if education was more inspiring for creating social change instead of complacency. But I guess part of the problem is people end up being teachers in universities, as opposed to activists—you are too busy teaching within universities instead of taking action. Maybe one of the (unintentional?) influences of academia is to dampen our enthusiasm for trying to change things.

AD: Definitely. After reading Edward Berman’s The Ideology of Philanthropy, I believe it is intentional. The way critical ideas and insights are domesticated to the classroom—passive learning—and entangled in bureaucracy is extremely dampening, not to forget the hostile work environments that are about administering and certifying students and climbing corporate ladders instead of focusing on liberatory teachings and, more so, practices. There are exceptions, but they are rare. Teachers seem to be sacrificing themselves to students—many entitled and seeking to get jobs—and to university bureaucracy and career politics. But, moving on, what has been the most challenging aspect or situation to running Active Distribution?

JA: Probably the most challenging thing about Active Distribution has been the logistics of where to store stuff and how much we can actually do. And what we can physically manage. Because it was always nonprofit, we weren't able and didn't want to pay rent, the storage was always based inside my bedroom, my flat or with my friends at times. The logistics of it all is part of what kept Active Distribution small. When someone get in contact say: “Hey, could you do our stuff?” It was like: “Well, no, because we don't have the space.” It wasn't quite as simple as that, but that's kind of how it went. And of course, at some point, that is when we decided that doing the records wasn't as important to us as doing books. And we stopped doing records. And then we stopped doing CDs, because they weren't as important either, and we didn't have the space because there were still lots of other record distributions around, but there were very few people doing the same kind of literature that we did. So yeah, the most challenging thing about Active Distribution has been literally managing it, storing it, physically getting the stuff in and out.

Also, I am terrible at doing accounts. So you could say the most challenging thing has been keeping track of money, which sadly, is something I never wanted to do, but we had e to do. It was important to me to treat money with as much disrespect as possible. It being, you know, the antithesis of anarchism in many ways. And so, it was part of the Active ethos that we would to help other people start up distros. I would give people books, pamphlets, zines and more on, should we say, credit—they could pay for it when they could. This was a great idea, and that's something I always want to do, and still do, but, unfortunately, there are a lot of people who get involved in things and thengive up very quickly or don't prove to be very reliable. So that has ended up with Active being owed shitloads of money from all kinds of people all over the world to this day. There are people I would dearly love it if they would at least admit to us that they didn't pay us, because it would just be nice to know that was the situation. ButI didn't keep very good accounts, and I never wanted to track people down about those kinds of things. So doing accounts is challenging. Did I do it properly? No. Did it matter in the long run? No, because to me, it was more important to get the stuff out there and then to worry about the finances. Obviously, you know, we had to get enough money to pay for things, but we are able to do that.

Active Distribution Titles

AD: It refreshing to hear this, this approach and practice that continues until today. Have you ever received any type of repression, censorship or persecution from running Active Distribution?

JA: Well, the simple answer is: No. Having said that part of active was the idea of doing a bookshop, info shop, at a squatted social center, etcetera, that I started with some friends in London, a place called Lee House in Hackney in 1989. During the course of that time, that's when I got to know and became friends with a guy who turned out many years later to be an undercover cop. That is some repression and persecution. But it wasn't specifically targeting Active. It was targeted at a whole bunch of us who were just doing things.

I am aware of various things that happened over years and that I have a police file. But, yeah, I guess in the terms of liberal Britain, what I do isn't considered something that they need to stop or clamp down on. There was a time when distributions like mine would not handle Animal Rights or Animal Liberation Front things because it just brought too much police attention. And that's probably true of Green Anarchist Magazine and things like that. I carried on doing that stuff. I guess I've always been of the opinion, yes, they know what I'm doing and, you know, unless I'd start doing things which endanger people's lives, they're not likely to, actually come through the door, which they may well have done if it was in some other countries.

AD: Related to action, what was one of your favorite demonstrations and/or riots you ever witnessed?

JA: I guess my favorite demonstration, in terms of the most memorable would be the Poll Tax Riot, which I was a little late to arrive. I was actually working that day and being a cynical anarchist, of course, I just thought it would just be another demo, another protest, but hey, that one was quite exciting. And I was in central London anyway, and so I was there, and yeah, witnessed quite a lot excitement, cops on the losing end for quite a long time. So that was memorable.

Also, the Stop the City marches. They were marches or demos, whatever you want to call them. They were great because that was the first time I witnessed a whole lot of kind of anarchist punks actually doing something other than going to gigs. And that felt, at the time, like: “Woohoo. This does really mean something.” There was some imaginative and interesting actions and leaflets and stuff going on. And, yeah, I witnessed that. I'll never forget, standing behind a row of people on the pavement, and the cops were trying to keep the road clear, and someone chucked a smoke bomb, and this female cop picked it up and went to throw it back into the crowd on the other side of the road, and failed miserably; and literally threw it into the back of the line of police on the other side of the road, which did cause quite a lot of merriment for those who witnessed it. But funnily enough, that was not reported the news. There was a picture of her throwing it, but not where it ended up. Anyway, yeah, let's not go down anecdote road.

Hmmm… [thinking]. I went to the Stonehenge events of 1986-87 because it was a protest, as opposed to a festival. You know, the cops had closed it down and were suppressing it. It was part of the whole Public Order Act, you know, attempt by the Tory Government to squash freedoms and activities of people they didn't like, like hunt saboteurs, squatters and travelers in this case, shall we say, alternative travelers. So yeah, and that's where I got nicked [arrested by police] and ended up having a fairly serious court case. But prior to getting nicked, they were interesting protests, they were fun, they were different. It was kind of like, you know, a roving band of punk vagabonds and hippies and that kind of thing, travelling around the Wiltshire countryside, establishing mini-festivals whenever we got a chance, because the cops wouldn't let us all meet up somewhere, and they have the festival, which used to happen at Stonehenge prior to 1985. So yeah, the Stonehenge riot

AD: You have been in this movement for some time, its great to hear about these events that I imagine many do not know, for example the Stonehenge riot or the Battle of the Beanfield—I did not know or forgot about this event. Coming to an end here, what are the most important books people would read in general and what Active Distribution titles or re-prints do you recommend?

JA: People should read whatever books they enjoy and excite them. And you know, the reason, one of the reasons that I publish and distribute all kinds of different books from different, shall we say, strands of anarchism because I'm well aware that people come to anarchism through different paths.

Personally, I think books like the Anarchy: A Graphic Guide by Clifford Harper and Anarchy Works by Peter Gelderloos are great starters and ways of educating yourself about anarchism and what may be possible. I also really enjoyed reading Max Stirner’s, The Ego and Its Own [/The Unique and Its Property] and Peter Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid, some of which I didn't quite get and skipped a bit when I first read it. But bits of it were really spoke to me as much as you know, any kind of Crass or Poison Girls lyric ever did.

I think some of those old books are really great, and partly because they show that this struggle is eternal. But there's no doubt that, you know, they may not be quite as relevant to the modern-day situation, which is why Anarchy Works is quite good, because that's up to date. The really new books, I haven't read much of it, but certainly David Graeber’s books seem to appeal to people and explain alternatives. The books I do, they are just ones which come to me for whatever reason. And one of the ones which I found very inspiring myself, and lots of feedback on it has been really good. It is the book about the Rojava struggle called: Worth Fighting For: Bringing the Rojava Revolution Home by Jenni Keasden and Natalia Szarek that illustrates the struggle in Rojava. And that is really interesting, because it's written by two activists who explore the whole notion of burnout, and then went to Rojava, or inspired to go to Rojava, by Anna Campbell experience, if I can call it that. And they write about what Rojava meant to them. And I think that's a really interesting book. Rojava isn't the answer for everybody. It hasn't been for me, but I can see why it could be, and I can see why that struggle is important.

I'll never forget listening to the BBC World Service Radio, and on January 1, 1994 when the Zapatistas emerged from the jungle and took over three towns in Chiapas. And I remember listening to this radio news and hearing the words Zapatistas. I'm thinking: “What? Zapatistas? That must be connected to Zapata?” And sure enough, it was. And that's a great bit of anarchism, and why history is important, because there is a modern-day group fighting for Indigenous autonomy inspired by a revolution from 100 years or so years earlier. And so, yeah, a book about the Zapatistas, and therefore, also a bit about Zapata, was one of the first things that I published, actually, I really need to redo that sometime. One of the first books I co-published was with Freedom Press, which was reprinting the book about Zapata himself, Zapata of Mexico, by Peter Newell, which is a great book, and I recommend that too! First, because it's well written and it's engaging, and it kind of explains why Zapata is such an influence and such an inspiration still to this day. So yeah, but I recommend the whole lot.

AD: Thanks for sharing and chatting Jon! I really appreciate it.

Visit: https://www.activedistributionshop.org/